In memory of Ensign Charles E. Butler, U.S. Navy

Lost at sea February 10, 1950

Photo courtesy of Jerry Wilson

Missing Navy Fighter Plane

Found Off Dana Point, CA

Dive Report

by Kendall Raine

The wreckage of a Navy F4U Corsair was located off the

coast of Dana Point in 2010 and has recently been

identified. Flown by Ensign Charles E. Butler, the

Corsair disappeared while flying in formation through

cloud cover on February 10, 1950. While the Navy

conducted an intensive search at the time, no evidence of

the plane or pilot was ever located and its location

remained a mystery until last year.

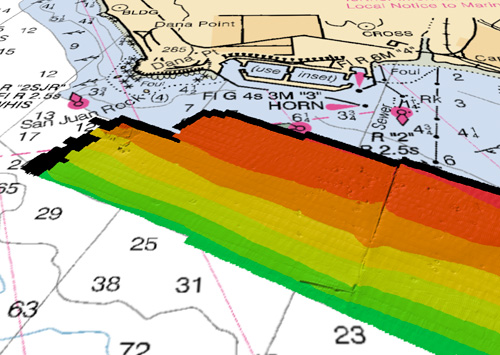

Operating on a request from the family of a missing

crewman who was lost aboard a twin-engine military

aircraft, Gary Fabian located a promising target on

multibeam sonar in the vicinity of the reported accident.

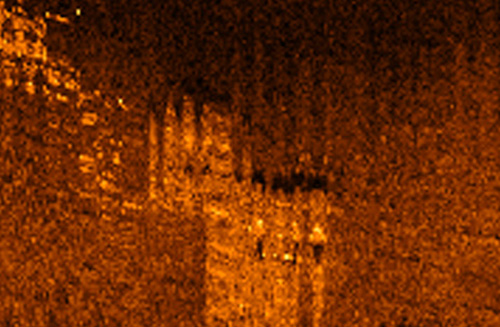

Capt. Ray Arntz conducted a side scan sonar evaluation of

the target and executed a quick bounce dive to confirm

the identity of the wreckage. Ray confirmed the presence

of a single radial aircraft engine of a type similar to

the plane we were looking for. His side scan image of the

site revealed numerous depressions within a 100 foot

radius. Apart from the one engine Ray found, the wreckage

was extremely fragmented. On December 7, 2010 John Walker

and I returned with to the wreck with Capt. Ray and Capt.

Kyaa Heller to conduct a scooter based video

documentation of the site in hopes of confirming the

exact ID of the aircraft. Our plan was to drop on the

most concentrated area of the wreck and then conduct a

circular scooter search of possible outlying sections of

wreckage. Our target plane ditched and we hoped to find

sections of the fuselage intact.

3D perspective view of Dana Point multibeam sonar survey.

Multibeam data provided by SANDAG. Image by Gary Fabian.

Larger Image

Side scan sonar image of aircraft debris field. Image

recorded by Ray Arntz.

As usual, we used a weighted drop line over the wreck

site in order to live boat the dive. There was about a

knot of current on the surface along with a south swell.

By the time John and I got in the water and squared away

we were 75 yards down current of the ball and were glad

to have the scooters to motor up to the drop point.

Visibility was limited and green on top and only opened

up below about 50 feet. As we neared the bottom I was

distressed to see the drop weight merrily bouncing across

the mud bottom. It was maybe 20 minutes since we dropped

the ball so I guessed we were between 400 and 600 feet

down current of the wreck site. Fortunately, the bottom

was soft mud and, with some effort, we were able to make

out a snail trail from the drop weight. We cranked up the

scooters and followed the trail for about five minutes

until we came across a large radial aircraft engine crank

case. Most of the cylinder heads were missing but the

four bladed prop was unmistakable along with two rows of

nine cylinders in a radial case. The engine was

consistent with a Wright R-3350, belonging to our target

plane. The four bladed prop was correct, as well.

Extending from the back of the block was a long crank

shaft which had two opposing impellers and a series of

reduction gears attached. These appeared to be part of a

supercharger which, again, was consistent with our target

plane.

All underwater photos by John

Walker

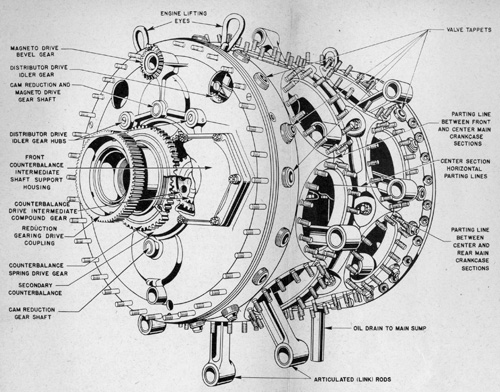

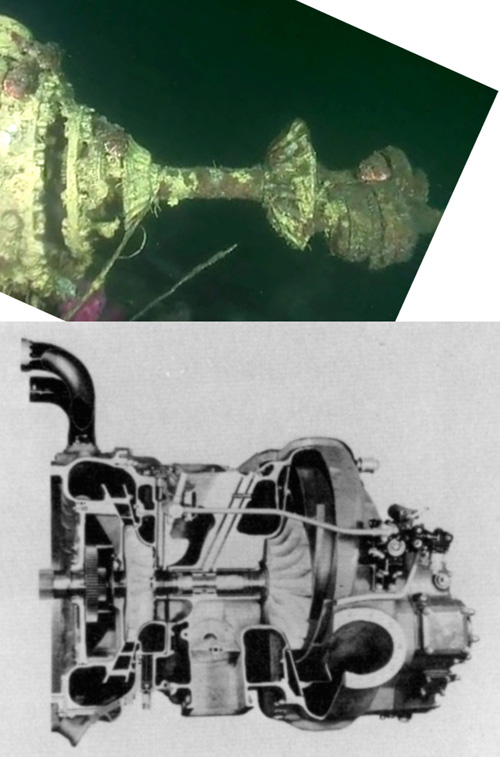

Eighteen cylinder radial engine with two-stage

supercharger

We searched the immediate area and came across what

looked like a landing gear assembly and a diamond tread

aircraft tire. A cylindrical oil cooler lay in the mud

alongside pieces of exhaust manifold, cylinder barrels

and other engine parts.

Aircraft tire with diamond tread pattern

Cylindrical oil cooler

Cylinder barrel and exhaust collector

The amount of debris fragmentation was disturbing since

we knew our target plane successfully ditched. The depth

was such that wave action shouldn’t have broken the

plane down so extensively. Nevertheless, we felt

increasingly sure we had our plane.

John and I then started a circular search. We tied into

the supercharger and scootered off on a bearing to the

most distant depression. After scootering 100 feet, we

started a circular sweep and came across numerous deep

depressions in the mud. We expected to find these

occupied by pieces of airplane, but all were empty of

aircraft debris. We returned to the main wreckage and

looked for additional parts.

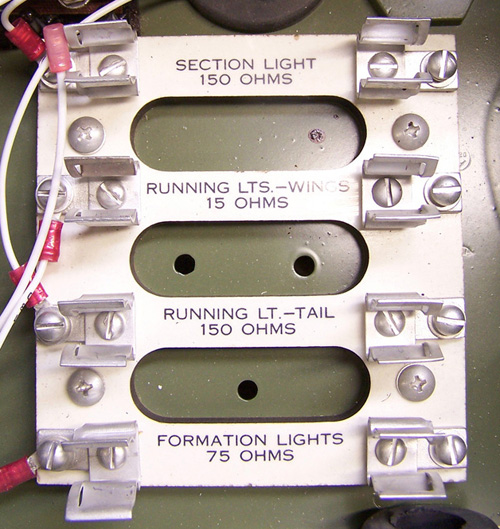

John shot extensive close-ups of the engine (the T-33

project had taught us close detail was vital in wreckage

ID.) He came across a piece of electrical panel which had

function and resistance markings on it. In most debris

searches only a few pieces of wreckage are unusual enough

to really drive the identification process. It seemed

John had found such a “Rosetta Stone.”

Aircraft electrical panel for exterior lighting circuits

We shot a bag and drifted through our deco. For some

reason, I couldn’t hear Sundiver II’s engines

overhead so I assumed Ray had realized the ball was

dragging early in the dive and was just drifting along

with our bag. Sure enough, he’d been tracking us

with sonar throughout the dive and was on top of the

bag when it surfaced.

Upon reviewing the video footage, we compiled a list of

evidence and believed we had indeed found our missing

plane. On the positive side the wreck was roughly where

it should be. We felt pretty sure the engine we found was

a Wright R-3350 and it also had a four bladed propeller.

What was disturbing was we hadn’t found the second

engine, wheel or any intact fuselage. Our plane ditched

and most of the crew survived. For that to happen the

fuselage had to have survived the ditching intact and

most likely the wing roots, engines and landing gear all

should have settled in close proximity on the bottom.

Since there was no evidence of nets on the wreck, the

chances of a fishing net having pulled away big sections

of the wreck seemed unlikely. Furthermore, we could find

no evidence that the piece of instrument panel John found

belonged to our plane.

Déjà vu all over again

A turn in the investigation came on December 10 when Gary

found detailed photos of a Wright R-3350 case along with

drawings of another engine which closely matched what

we’d found. The drawings clearly indicated what we

found was not a Wright R-3350, but a Pratt & Whitney

R-2800. This was the T-33 all over again. Having found a

plane where we expected it to be, we momentarily fell

into the trap of assuming that 2+2 equaled 4. It

didn’t.

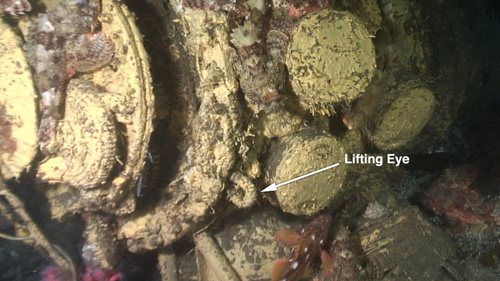

Lifting eye on engine

Valve tappets on engine

Crankcase drawing of Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engine

R-2800’s were never used on our target plane. They

were used on various other types including the F4U, F6F,

F8F, P-47, DC 6, B-26 and others. Our attention then

turned to the supercharger. With two opposing impellers,

the supercharger was a conventional two-stage two-speed

design consistent with the F4U-4 Corsair and the F6F

Hellcat. The Hellcat only had a three bladed propeller;

however. Our plane has a Hamilton Standard four bladed

propeller.

Comparison of engine (top) and a Pratt & Whitney

R-2800 supercharger cutaway (bottom)

Remains of a Hamilton Standard 4-bladed propeller

The “dash 4” was also the first Corsair to

utilize a four bladed prop. Corsair’s were flown

extensively by Marine Corps and Naval aviators during

both WWII and Korea. With a service career of ten years,

there were lots of Corsairs buzzing around Southern

California. We then turned to aviation expert Pat Macha

to see if he had any records of Corsair losses in the

immediate area. Pat sent us everything he had, but

nothing was directly on point.

The Picture Emerges

Finally, after days of searching Gary found two Los

Angeles Times articles from 1950 describing the loss of

an F4U Corsair and subsequent search in the Dana Point

area. Gary relayed the information back to Pat who

contacted Craig Fuller at AAIR who was able to get us the

Navy accident report within hours.

The aircraft was an F4U-4B piloted by Ensign Charles

E. Butler based at NAS North Island, San Diego, CA.

Planes Search

Coast for Navy Fighter Pilot

Los Angeles Times

February 12, 1950

An intensive air-sea search for an F4U Navy fighter

missing since 2:30 pm Friday was in progress yesterday

with 19 planes, Coast Guard cutters and a helicopter

combing the rocky coastline near Dana Point. Naval

Officials said the plane was on a training flight from

the Naval Air Station at North Island, San Diego. The

pilot and sole occupant was identified as Ensign Charles

Emery Butler, 22, of Baggs, Wyo. Butler was flying in

formation with another Navy ship over the coastline

Friday afternoon.

Search for

Missing Plane Abandoned

Los Angeles Times

February 14, 1950

SAN DIEGO, Feb 14 (AP)- Search was abandoned today for a

missing Navy F4U Corsair fighter plane missing since

Friday. Navy officers expressed belief the plane, piloted

by Ensign C.E. Butler, 22, of Baggs, Wyo., crashed into

the sea after disappearing in clouds near Santa Ana from

other fighters in a training flight of

five.

Now we were getting somewhere. We had a documented

missing aircraft that matched the engine, supercharger

and propeller configuration of the wreck. The tire and

oil cooler are also consistent with an F4U. But we still

had a piece of instrument panel which decidedly did not

match anything visible inside the cockpit of any F4U

variant. The instrument panels in the F4U are black metal

with white lettering. The panel observed on the wreck

appears to be white plastic with black lettering. The

resistance markings on the panel matched the

builder’s specifications for the Corsair lighting

circuits, so we were pretty confident we had a piece of

an F4U. Without placing the piece; however, we

didn’t want to go public with the story. We’d

mis-ID’d the plane once and were uncomfortable with

a piece that didn’t fit.

Finally, the “Rosetta Stone” spoke. On

January 3, 2011, Julie Chaminand from ClassicFighters.org relayed a photo

from Commander Doug Matthews of a resistor block

currently being installed in an F4U restoration. The

photo was taken for us by aircraft restoration expert

John Lane at Airpower Unlimited in Jerome, ID. It was

a perfect match. The resistor block mounts inside the

electrical control box of an F4U Corsair. No doubt

about it. No wonder we couldn’t find it in any

photos. At this point we had eliminated the only

remaining contradiction.

F4U Corsair resistor block. Photo courtesy of John Lane.

All the evidence we had indicated this was the F4U-4B

piloted by Ensign Butler. Nothing we had suggested

otherwise. From the newspaper clippings we started our

search for surviving relatives in Baggs, Wyoming, Ensign

Butler’s home town. Through the fine work of Dave

Mihalik, retired Assistant Police Chief of Irvine, CA,

and a member of Pat Macha’s aircraftwrecks.com search team, we

were able to locate Ensign Butler’s childhood

friend. Through the help of Baggs resident Linda

Fleming, Dave made contact with Jerry Wilson, 82, of

Yuma, AZ. Jerry told us Ensign Butler was an only

child and had no known living relatives. Shortly after

Ensign Butler’s disappearance Jerry traveled to

North Island, San Diego to inquire about the fate of

his friend. He spoke with a Navy chaplain, but was

given little information and was refused entrance to

the base. With nothing to go on, Jerry went home and

commissioned a memorial in Charles' name now located

in the cemetery in Baggs, Wyoming. In the waning years

of his own life, Jerry was very appreciative to learn

the final resting place of his missing friend Charles

Butler.

F4U Corsair plane wreck discovery from John Walker on Vimeo.