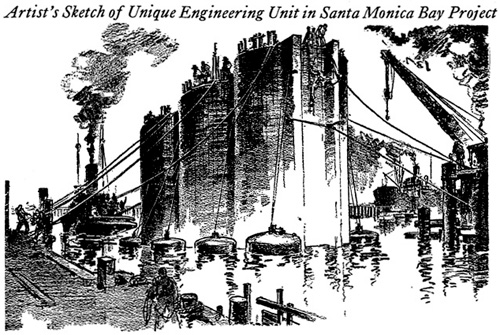

Scene at Long Beach when the first completed caisson in the

$690,000 Santa Monica Yacht Harbor project was successfully

launched.

Image from the Los Angeles Times Mar. 12, 1933

The

Caissons

Two man-made structures lie on the ocean floor just a few

short miles from Los Angeles Harbor. Separated by less than

a half mile, these identical structures, composed of three

vertical concrete cylinders, span a distance over 100 feet

and tower more than 30 feet above the seabed. "The

Caissons”, as they are commonly known, are a popular

destination for SCUBA divers capable of reaching their

depths over 140 feet below the surface.

While they do resemble a caisson used in bridge

construction work, their actual purpose has only been

speculated. Were they used to protect Los Angeles Harbor

during WWII? Were they used during the construction of the

Vincent Thomas Bridge in the 1960’s? Are they some

type of storage tanks? Or were they used as anchors for

offshore oil drilling platforms? How did they get here and

when were they sunk? These are some of the questions

surrounding the mystery of the Caissons that have remained

unanswered until now.

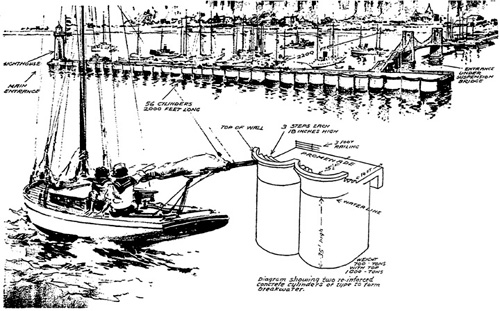

Image from the Los Angeles Times Dec. 13, 1931

Colorful

Haven Visioned at Yacht Harbor

The caissons or “concrete cribs” were part of

the original plans to construct the 2000 foot Santa Monica

Yacht Harbor Breakwater in 1933. The $690,000 project

called for eighteen such caissons to be placed side by

side, filled with sand, and anchored to the seafloor with

steel pilings. Designed by Howard B. Carter, City Engineer

of Santa Monica, each steel reinforced concrete caisson,

weighed 2100 tons, measured 111 feet long, thirty-five feet

wide at the base, thirty-six feet high, with a diameter of

twenty-eight feet at the tubular sides.

The exteriors of each unit would present curved surfaces to

the forces and currents of the surging sea. The three

arches on each side of the caisson would distribute the

water stresses on the unit equally, exactly as arches have

been used to absorb stresses equally in buildings and

bridges for centuries.

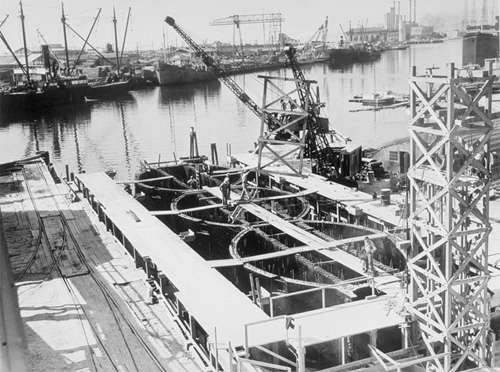

First caisson under construction.

Courtesy of the Santa Monica Public Library Image Archives

The giant caissons were built in a specially designed

graving dock at the Graham Brothers’ yard in Long

Beach, by the Puget Sound Bridge and Dredging Company, the

general contractors for the project. Each unit was

constructed with a false bottom for floating purposes.

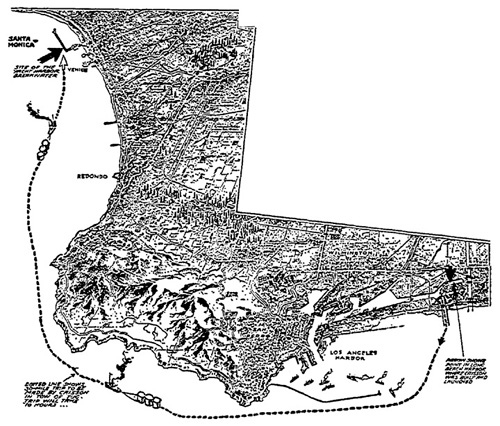

Image from the Los Angeles Times Mar. 12, 1933

Once built and allowed to harden for several weeks, the

first caisson was floated and towed by tug under the Edison

drawbridge and then the thirty miles around the coastline

to its final position in Santa Monica Bay. The occasion

marked the first time in the United States that an attempt

had been made to float a similar concrete construction in

an open sea.

Photo from the Los Angeles Times Mar. 10, 1933

Concrete

Ship

Launching at Long Beach of the first crib for the Santa

Monica Yacht Harbor breakwater and inset, watching the

operations, Howard B. Carter, City Engineer of Santa

Monica, W. F. Way, engineer in charge, and N. S. Ross,

associate in the contracting firm of Puget Sound Bridge and

Dredging Company and W. F. Way, Inc., of Los Angeles.

As the crib was launched it bore the name of John Morton,

Commissioner of Public Works of Santa Monica. Each

following unit, which were to be completed at a rate of one

a week, were to be named after some beach city official.

Photo from the Los Angeles Times Mar. 26, 1933

Floating

Breakwater Takes Trip to Home in Sea

Tugs stand by after towing caisson from Long Beach while

engineer on end of Santa Monica pier lines up spot on which

to sink caisson.

Close-up of caisson being lowered into position.

Photo from the Los Angeles Times Mar. 26, 1933

Ready to

Visit Davey Jones Locker

The plans for a crib type breakwater would come to an

abrupt end soon after the first caisson was lowered into

position. Sand scouring beneath the structure had caused

the unit to crack and soon the central cylinder collapsed.

The remains of the caisson were declared a menace to

navigation and cleared away with dynamite. A traditional

rock-mound type breakwater was eventually adopted in favor

of the crib type design.

At the time of the first caissons’ failure, three

completed caissons were still waiting at Long Beach for

installation. Obviously this would never happen and on May

27, 1935 the remaining sections were towed out to sea and

sunk. The location of the third caisson is not known, but

due to the close proximity of the dump site to the San

Pedro Valley, it’s possible the third caisson was

sunk in deep water and is gone forever.

Navy records from 1942 indicate that the U.S.S. Gilmer made

sonar contact and a subsequent depth charge attack on a

stationary object on the seafloor believed at the time to

be a possible enemy submarine. The range and bearing given

in the report matches precisely with the location of

Caisson #2. This attack would account for the severe damage

to one end of the caisson that is visible today.

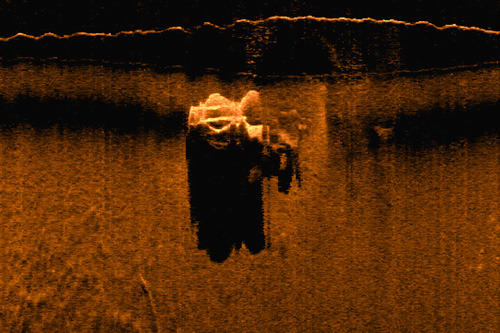

Side

scan sonar image of Caisson #2. The far right cylinder of

the caisson is completely destroyed along with half of the

center cylinder. The left cylinder is intact and the two

crossmembers are easily visible. The large acoustic shadow

gives a good sense of the 36 foot vertical relief of the

structure.

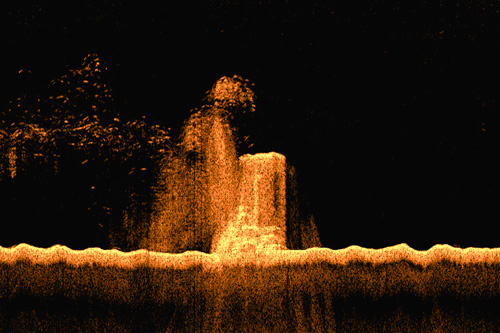

A

traditional sonar recording of Caisson #2. The sheer

vertical sides of the caisson are very evident as well as

the debris pile from the collapsed cylinders at the base of

the structure. A large population of fish make the Caissons

their home.

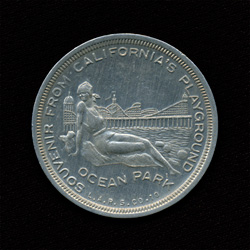

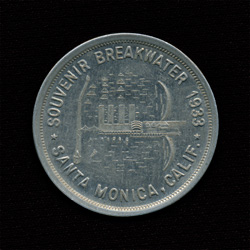

This

1933 Santa Monica Breakwater So-Called Dollar (HK-687) was

struck off to commemorate the start of the breakwater

project. The front of the coin (left) shows a young woman

sunbathing on the beach next to the Santa Monica Pier. The

back of the coin (right) depicts the completed breakwater

and yacht harbor. Note the suspension bridge connecting the

end of the pier to the breakwater. These coins can also be

found in brass, nickel, and a rare blue aluminum

version.